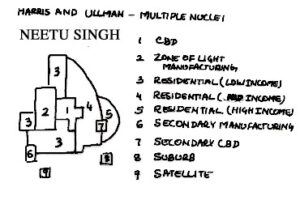

With the expansion of an urban area more specialized nuclei can emerge. In all major urban areas & cities the CBD is located near the inter city transport. The CBD may not be in the center of city but can be developed at an edge of city or built up areas. It depends on the asymmetrical growth of city or urban area. In an urban area Industry, whole sailing & ware housing develops near inter city transport areas. Where as the heavy industry is located away from the main part of the city or urban areas. As the city size increases the residential districts will show an increasing differentiation. In this way the cultural center and entertainment centers or suburban business districts will take a form of other nuclei in the city. Beyond the built up area, settlements which develops as a repercussion of rail services for commuters and private car use. This theory also explains about the irregular pattern of urban landuse because development occurs from different centers, which means the particular pattern of landuse emerge at each different urban area with no common basic pattern of development.

Conclusively; all the theories explained above adds to our knowledge of the cities. Because when the sectors developed in cities and the transit & highways elongated the landuse patterns; eventually a nuclei develop or more appropriately said that transportation and economic development added new dimensions to the landuse of the city. Therefore whenever the landuse patterns of a large old city is evaluated; that has gone through such changes; it may be possible to find all these landuse patterns. It is very rare that contemporary cities show entirely one theory of the landuse change. Finally it is also evident from these theories or models of urban Growth that it only focused on the affects of growth on urban development pattern. Whereas the causes of urban growth is not addressed in these theories; because all theories have an assumption that an urban area will grow in size or physical morphology will change & the growth of city is taken for granted.

Thus conclusively the current discussion leads us to following realities.

· Urban growth can be spontaneous on its own or planned growth as directed by the authorities.

· The concept of planning is to provide a vision for future well before the people actually settle in the settlements and planning may also be appropriate enough to facilitate the process of housing the poor in the city.

· The basic planning component is that incompatible land uses should not be allowed or located together.

· Circulation, transport, infrastructure and land use management are the basic tools of planning to guide the urban growth and transformation in the city.

· Suburban growth shall be seen as the series of phases through which a particular location passes or it is the development which proceed from an open land to mature urban development.

· The objectives of sound planning should be to develop a set of simple guidelines, or principles which should be comprehensive and adaptable to changing conditions of the future.

URBAN MORPHOLOGY

The city is a global phenomenon. It is also a regional and cultural variable. The descriptions and models that we have used to study the functions, land use arrangements, suburbanization trends, and other aspects of the U.S. city would not in all or even many-instances, help us understand the structures and patterns of cities in other parts of the world. Those cities have been created under different historical, cultural, and technological circumstances. They have developed different functional and structural patterns, some so radically different from our U.S. model that we would find them unfamiliar and uncharted landscapes indeed. The city is universal; its characteristics are cultural and regional

The North American City

Even within the seemingly homogeneous North American culture realm, the city shows subtle but significant differences not only between older eastern and newer western U.S. cities, but between cities of Canada and those of the United States. Although the urban expression is similar in the two countries, it is not identical, and truly “North American city” is more a myth than a reality. The Canadian city, for example, is more compact than its U.S. counterpart of equal population size, with a higher density of buildings and people and a lesser degree of suburbanization of populations and functions. Space saving multiple family housing units is more the rule in Canada, so a similar population size is housed on a smaller land area with much higher densities, on average, within the central area of cities. The Canadian city is better served by and more dependent on mass transportation than is the U.S. city. Since Canadian metropolitan areas have only one-quarter the number of miles of expressway lanes per capita as U.S. MSAs-and as least as much resistance to constructing more suburbanization of peoples and functions is less extensive north of the border than south. It is likely to remain that way.

In social as well as physical structure, Canadian-United States contrasts are apparent. While cities in both countries are ethnically diverse, Canadian communities, in fact, have the higher proportion of foreign born – U.S. central cities exhibit far greater internal distinctions in race, income, and social status and more pronounced contrasts between central city and suburban residents. That is, there has been much less “flight to the suburbs” by middle-income Canadians. As a result, the Canadian city shows greater social stability, higher per capita average income, more retention of shopping facilities, and more employment opportunities and urban amenities than its U.S central city counterpart. In particular, it does not have the rivalry from well-defined competitive “outer cities” of suburbia that so spread and fragment United States metropolitan complexes.

The Western European City

If such significant urban differences are found even within the lightly knit North American region, we can only expect still greater divergences from the U.S. model at greater linear and cultural distance and in countries with long urban traditions and mature cities of their own. The political history of France, for example, has given to Paris an over-whelmingly primate position in its system of cities. Political, economic and colonial history has done the same for London in the United Kingdom. On the other hand, Germany and Italy came late to nationhood, and no over-whelmingly dominant cities developed in their systems.

Nonetheless, a generally common heritage of medieval origins, renaissance restructuring and industrial period extensions has given to the cities of Western Europe features distinctly different from those of cities in other regions founded and settled by European immigrants. Despite wartime destructions and postwar redevelopments, many still bear the impress of past occupants and technologies, even back to Roman times in some cases. Although the European urban pattern we see today is primarily the product of the industrialization of the 19th and 20th centuries, frequently the location and shape of the settlement, the street pattern, and the layout of the older sections are more a reminder of the distant past than a reflection of modern requirements and responses. An irregular system of narrow streets may be retained from the random street pattern developed in medieval times of pedestrian and pack-animal movement. A system of main streets radiating from the city center and cut by circumferential “ring roads” tells us the location of high roads leading into town through the gates in city walls now gone and replaced by circular boulevards. Broad thoroughfares, public parks, and plazas mark renaissance ideals of city beautification and the esthetic need felt for processional avenues and promenades.

Although each is unique historically and culturally, Western European cities as a group share certain common features that set them apart from the United States model, though they are less far removed from the Canadian norm. Cities of Western Europe have, for example, a much compact form and occupy less total area than American cities of comparable population; most of their residents are apartment dwellers. Residential streets of the older sections tend to be narrow, and front, side, or rear yards or gardens are rare. European cities developed for pedestrians and still retain the compactness appropriate to walking distances. The sprawl of American peripheral and suburban zones is generally absent. At the same time, compactness and high density do not mean skyscraper skylines. Much of urban Europe predates the steel-frame building and the elevator. City skylines tend to be low, three to five stories in height, sometimes (as in central Paris) held down by building ordinance or by prohibitions on private structures exceeding the height of a major public building, often the central cathedral.

Compactness, high densities, and apartment dwelling encouraged the development and continued importance of public transportation, including well-developed subway systems. The private automobile has become much more common of late, though most central city areas have not yet been significantly restructured with wider streets and parking facilities to accommodate it. The automobile is not the universal need in Europe that it has become in American cities. Home and work are generally more closely spaced in Europe – often within walking or bicycling distance -while most sections of towns have first-floor retail and business establishments (below upper-story apartments), bringing both places of employment and retail shops within convenient distance of resistances.

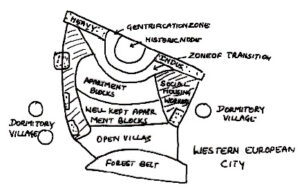

A very generalized model of the social geography of the Western European city has been proposed. Its exact count part can be found nowhere, but many of its general features are part of the spatial social structure of most major European cities. In the historic core, now increasingly gentrified, residential units for the middle class, the self-employed, and the older generation of skilled artisans share limited space with preserved historic buildings, monuments, and tourist attractions. The old city fortifications may mark the boundary between the core and the surrounding transitional zone of substandard housing, 19th century industry, and recent immigrants. The waterfront has similar older industry; newer plants are found on the periphery. Public housing and some immigrant concentrations may be near that newer industry, while other urban socioeconomic groups aggregate themselves in distinctive social areas within the body of the city. The European city does not characteristically feature the ethnic neighborhoods of U.S. cities although some, like London, do. Rather, its guest workers from Eastern Europe, the Near East, and North Africa tend to be relatively dispersed rather than concentrated. Nor is it characterized by inner-city deterioration and out-migration. Its core areas tend to be stable in population and to attract rather than repel the successful middle class and the upwardly mobile, conditions far different from comparable sections of older U.S. central cities.

Cities of Eastern Europe make up a separate urban class, the socialist city. It is an urban form that shares many of the traditions and practices of Western European cities, but it differs from them in the centrally administered planning principles that have been designed to shape and control both new and older settlements. The particular concerns have been, first, limitation on size of cities to avoid super city growth and metropolitan sprawl; second, assurance of an internal structure of neighborhood equality and self-sufficiency; and third, strict land use segregation. The socialist city has fully achieved none of these objectives, but by attempting them it has emerged as a distinctive urban form.

Within the vast domain of the Soviet Union, where the planning philosophies of the socialist city were formulated, urbanization has proceeded rapidly during the period of communist rule. Urban population has increased from about 18% (1917) to 66% (1989) of total population, some 150 million new urban residents have been accommodated, and over 1500 new or largely rebuilt cities have been created in general accordance with the socialist city model. Although the Eastern European countries taken into the Soviet bloc following World War II were in general, more urbanized than the USSR had been, they too have experienced and acceleration of urbanization on the Soviet model with recent industrialization. As a group, they add another 71 million urbanites to the 191 million Soviet city residents (1989).

Although city planning In the Soviet Union has not been rigorously or consistently applied, often thwarted because city governments responsible for planning are powerless to control or change site decisions made by economic ministries – the accepted planning guidelines have made themselves evident in the urban landscape. In general structural terms, the socialist (Soviet) city is compact, with relatively high building and population densities reflecting the nearly universal apartment dwelling, and with a sharp break between urban and rural land uses on its periphery. Like the older-generation Western European city, the socialist city depends exclusively on public transportation.

It differs from its Western counterpart, of course, in its purely governmental rather than market control of land use and functional patterns. That control has dictated that the central area of cities should be reserved for public use, not occupied by retail establishments or office buildings on the Western, capitalist model. A large central square ringed by administrative and cultural buildings is the preferred pattern. Nearby, space is provided for a large recreational and commemorative park. Neither a central business distinct nor major outlying business districts are required or provided in the socialist city, for residential areas are expected to be largely self-contained in the provision of at least low-orders goods and services, minimizing the need for a journey to centralized shopping locations. Those residential areas are made up of “micro districts,” assemblages of uniform apartment blocks housing perhaps 10,000 to 15,000 people, surrounded by broad boulevards and containing centrally sited nursery and grade schools, grocery and department stores, theaters, clinics, and similar neighborhood necessities and amenities. Plans call for effective separation of residential quarters from industrial districts by landscaped buffer zones, but in practice many micro-districts are built by factories for their own workers and are located immediately adjacent to the workplace.

Since micro-districts are most easily and rapidly constructed on open land at the margins of expanding cities, high residential densities have been carried to the outskirts of town. The distance decay curve of declining population densities outlined does not apply to the socialist city. Although egalitarian planning principles demand uniformity in the housing stock and a total prohibition of any form of residential segregation, in practice uniformity is not achieved and segregation does occur. To the extent that the housing stock is built by industrial and institutional entities for their own workers (perhaps a third or more of all nits), segregation of housing by place of employment is automatic. Further, some sections of most cities are seen as more prestigious and desirable than others, and those citizens able through income or influence to locate within them do so, establishing elite neighborhoods in a city equals.

The Soviet ideal has long been for cities to achieve but not exceed a size in which (1) the provision of public (2) reasonable scale economies of agglomeration are possible, and (3) the diseconomies of peripheral spread, congestion, commuting costs, pollution, and the like are avoided. In particular, massive metropolitan sprawl and conurbations are to be avoided. Since domestic migration is controlled and Soviet citizens (and Eastern Europeans in general) must have permits to live and work in given locales, control of city size would appear simple. In reality, it has not proved so – again because economic ministries can make vocational decisions without reference to individual city plans or goals. Thus, the Moscow metropolitan area approximates 10 million in an urban sprawl in many ways reminiscent of that of Western cities, and other major socialist cities show similar tendencies to spread.

Cities in the Developing World

Still farther removed from the United States urban model are the cities of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, where industrialization has come only recently or not at all where modern technologies in transportation and public facilities are barely known or sparsely available, and where the structures of cities and the cultures of their inhabitants are far different from the urban world familiar to North Americans. The developing world is vast in extent and diverse in physical and social content; generalizations about it or its urban landscapes lack certainty and universality. Islamic cities of North Africa, for example, are entities sharply distinct from the black African, the Southeast Asian, or the Latin American city. Yet, by observation and consensus, some common features of Third World cities are recognizable. All, for example, have endured massive in-migrations from rural areas. As a result, most are ringed by vast squatter settlements high in density and low in public facilities and services. All, apparently, have populations greater than their formal functions and employment bases can support. In all, large numbers support themselves in the ‘informal” sector as snack-food vendors, peddlers of cigarettes or trinkets, street-side barbers or tailors, errand runners or package carriers and the like outside the usual forms of wage labor.

But the extent of acceptable generalization is limited, for the backgrounds, developmental histories, and current economies and administrations of Third World cities vary greatly. Some are still pre-industrial, without a central commercial core, without industrial districts, without public transportation, without any meaningful degree of land use separation. Some are the product of Western colonialism, established as ports or outposts of administration and exploitation, built by Europeans on the Western model, though increasingly engulfed by later, indigenous urban forms. In some, Western-style skyscraper central areas and commercial cores have been newly constructed. In others, commerce is conducted in different forums and formats.

Wherever the automobile and modern transport systems are an integral part of the growth of Third World cities, the metropolis begin to take on Western characteristics. On the other hand, in places such as Bombay (India), Lagos (Nigeria), Jakarta (Indonesia), Kinshasa (Zaire), and Cairo (Egypt), where modern roads have not yet made a significant impact and the public transport system is limited, the result has been overcrowded cities centered on a single major business district in the old tradition. In such societies, the impact of urbanization and the responses to it differ from the patterns and problems observable in the cities of the United States.

The developing countries, emerging from earlier dominantly subsistence economics, have experienced disproportionate population concentrations, particularly in their national and regional capitals. Lacking or relatively undeveloped is the substructure of maturing, functionally complex smaller and medium-sized centers characteristic or more advanced and diversified economies. The primate city dominates their urban systems. Greater Cairo contains nearly 30% of Egypt’s total population; 30% of all Nicaraguans live in Managua; and Baghdad contains 24% of the Iraqi populace. Vast numbers of surplus, low-income rural populations have been attracted to these developed seats of wealth and political centrality in type hope of finding a job. Although attention may be lavished on creating urban cores on the skyscraper model of Western cities, most of the new urban multitudes have little choice but to pack themselves into squatter shanty communities on the fringes of the city, isolated from the sanitary facilities, the public utilities, and the job opportunities that are found only at the center. In the sprawling slum district to Nairobi, Kenya, called Mathare Valley, some 250,000 people are squeezed into 6 square miles (15.5 km2) and are increasing by 10,000 per year. Such impoverished squatter districts exist around most major cities in Africa, and Latin America. Proposed models of third World urban structure demonstrate the limits of these generalizations. The same models (and others) help define some of the regional and cultural contrasts that distinguish those cities.

The port and its associated areas in the large composite Southeast Asian city were colonial creations, retained and strengthened in independence. Around them are found a Western-style central business district with European shops hotels, and restaurants; one or more “alien commercial zones’ where merchants of the Chinese and, perhaps, Indian communities have established themselves; and the more widespread zone of mixed residential, light industrial, and indigenous commercial uses. Central slums and peripheral squatter settlements house up to two-thirds of the total city population. Market gardening and recent industrial development mark the outer metropolitan limits.

The South Asian city appears in two forms – the internal structure of the colonial-based city, making clear the spatial separation of native and European residential areas, the mixed-race enclave between them, and the 20th century new-growth areas housing the wealthier local elites; and the traditional bazaar city, its center focused upon a crossroads around which the houses of the wealthier residents are situated. Merchants live above or behind their shops, and the entire city center is characterized by mixed residential, commercial, and manufacturing land uses. Beyond the inner core is, first, an upper-income residential area shared (but not in the same structures) with poorer servants.

Still farther out are the slums and squatter communities, generally sharply segregated according to ethnic, religious, or caste status or native village of their inhabitants.

The Latin American city is more thoroughly “Westernized” than its Asian or African counterparts, but it shows many of the same land use arrangements. The focal core is a central business district on the North American and European model, served by a well-developed mass transit system and having the full range of urban services and amenities. It therefore retains its attraction for middle and upper-income residents who contribute to its upgrading and modernization through new apartment construction. A commercial “spine,” essentially an extension of the CBD, leads away from the core. Bordering it in an ever-widening elite sector are the upper-income housing districts, the best theaters and restaurants, modern office buildings, exclusive shops, major boulevards, and wealthiest suburbs. The area occupied by the urban elites far exceeds their proportion of total population.

The far greater numbers of lower-income and destitute urban residents occupy the concentric zones spaced around the core. The inner “zone of maturity” houses the middle class in solid structures, well maintained. The “in-situ” zone is one of more modest and mixed residential quality, under continuing reconstruction and upgrading as its residents improve their economic status. At its outer margins, however, it fades into the “peripheral squatter settlements” zone, the outer ring housing in the urban area’s worst shantytowns and sums the most impoverished and most recent in-migrants to the city.

Each of these models presents a variant of the developing world’s urban dilemma: an urban structure not fully capable of housing the peoples so rapidly thrust upon it. Populations of Third World cities in the late 1980s were growing by 3.5% annually, three times faster than urban growth in the Western world. The extreme case was Africa, where a 5% annual growth rate implied a doubling of city populations in 14 years. These numerical increases exceed urban support capabilities, and unemployment rates of 25% are common in cities of the developing world. There is little chance to reduce them as additional millions – through natural increase and in-migration, swell cities already overwhelmed by poverty, lack of sanitation facilities, inadequate water supplies, antiquated public transportation, and spreading slums. The problems, cultures, environments, and economies of Third World cities are tragically unique to them. The urban models that give us understanding of United States cities are of little assistance or guidance in such vastly different culture realms.

Summary

The city is the essential functional node in the chain of linkages and interdependencies that marks any society or economy advanced beyond the level of subsistence. The more complex and functionally integrated the society, the greater the degree of specialization and exchange that it demands for its maintenance, and the more urbanized it becomes. Although cities are among the oldest marks of civilization, only in this century have they become the home of the majority of the people in the industrialized countries and the inhospitable place of refuge for uncounted millions in modernizing Third World economies. At the global scale, four major world urban regions have emerged; Western Europe, South Asia, East Asia and North America. Within those regions, metropolitan expansion has created massive conurbations.

All cities growing beyond their village origins take on functions uniting them to the countryside and to a larger system of cities; all, as they grow, become functionally complex. Their economic base may become diverse and is comprised of both basic and service activities. The former represent the functions performed for the larger economy and city system, the later those present to satisfy the needs of the urban residents themselves. Functional classifications distinguish the economic roles of cities, while simple classification of them as transportation and special function cities or as central places helps define and explain their functional and size hierarchies and the spatial patterns they display within a system of cities.

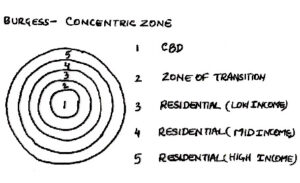

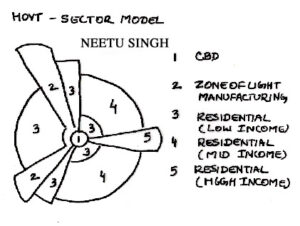

As North American urban centers expanded in population size and diversity, they developed more or less structured land use patterns and social geographies based on market allocations of urban space, channelization of traffic, and largely voluntary socioeconomic aggregation. The observed regularity of land use arrangements has been summarized for U.S. cities by the concentric zone, sector, and multiple-nuclei models. Social area counterparts of land use specializations were based on social status, family status and ethnicity. Since 1945, these older models of land uses and social areas have been modified by the suburbanization of people and functions that has led to the creation of new and complex outer cities and to the deterioration of the older central city itself.

Urbanization is a global phenomenon, and the U.S. models of city systems, land use structures, and social geographies are not necessarily or usually applicable to other cultural contexts. Models descriptive of Third World city structures do little to convey the nature of their universal dilemmas of intense overcrowding, poverty, and inadequate physical structure.

Go Back